Through the Depression and Recession, Fourth-Generation Family Stained Glass Company Thrives in Columbus

July 14, 2017

COLUMBUS, Ohio — Stained glass has always been a fixture in Andrea Helf Reid’s life. When she was a kid, summers meant traveling to different parts of the country for stained-glass conventions, which would roll into family vacations. Closer to home, she’d help out at the Helf family business, Franklin Art Glass Studios Inc., in German Village — working in the store, cutting pattern pieces for the artists, sweeping the warehouse floors and any other odd job that needed done.

“It made for a really great education in glass,” Helf Reid says. “Having seen a lot of different glass a lot of places and knowing a lot of other artists and studios throughout the nation was kind of an indirect exposure to everything. But it was never, like, forced or never pressured, which was really nice.”

By the time she started college at Wittenberg University in Springfield, Helf Reid knew she wanted to come back to Columbus and work at the family business. Founded in 1924, Franklin Art Glass has a rich local and regional history. And even before Franklin Art Glass, her family was making stained glass in Columbus.

“I’m an only child, so it was kind of one of those things where, if I didn’t come here it was OK, but … it would mean having to sell,” she says. “We’re a really small family.”

With her post-graduation plans in mind, Helf Reid decided to study both business and art. She worked with an advisor from each area of study to create an interdepartmental degree, which was then approved by the provost.

“It worked out really well,” she says of her bachelor of arts degree.

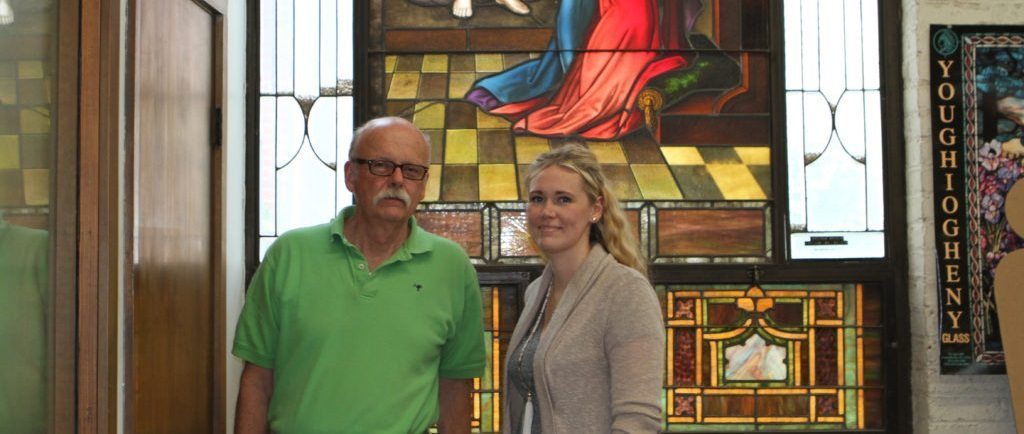

Since graduating in 2003, Helf Reid has been continuing her family’s legacy at the Sycamore Street studios. While her title is vice president of Franklin Art Glass Studios Inc., she does a little bit of everything, much like when she was younger. Today, her roles include part-time designer, bookkeeper and marketing and social media manager.

Turbulent Times

Stained glass goes back five generations in the Helf family. It all started with Henry Helf, who worked as the shop foreman at Von Gerichten Art Glass Co. in Columbus until the company closed in 1931.

Henry passed his love of glasswork on to his son Henry “Elmore” Helf, who — along with Wilhelm Kielblock and Wilhelm Kielmeier — founded Franklin Art Glass Studios Inc. on Spring Street downtown in 1924.

At the time, the country was on the brink of the Great Depression, which lasted for about a decade, starting in the late 1920s. Henry wasn’t getting work at Von Gerichten, so he filled his time by drawing intricate window designs for Franklin Art Glass.

“And then they would turn around and use [the drawings] as their sales portfolio or catalog later on,” Helf Reid says. “So it turned out to be a pretty useful tool, that he did kind of doodle so much.”

The economic downtown meant little work for the fledgling company, so Kielblock and Kielmeier left Franklin Art Glass. Kielblock was an artist and had little interest in running a business, anyway. But their departure was amicable, and Kielblock even set up shop at Franklin Art Glass Studios, producing glasswork under his own company, Ohio Trade Studio.

“He did a lot of really neat stuff,” Helf Reid says of Kielblock. “He just kind of produced what he wanted when he wanted, and then we would pay him to do the [jobs] we were doing. And he worked here until his death.”

Despite the Depression, Franklin Art Glass survived and, eventually, thrived. When Kielblock and Kielmeier left, there were less people to pay. Plus, the Helf family already had established connections in the industry.

“Both Henry and Elmore were really involved in the Stained Glass Association of America,” Helf Reid says. “They held the first convention here in Columbus. And we held the 100th convention here in Columbus, back in 2003, as kind of a celebration of that. But I think that being really involved in that kind of national organization — at the time, those trade organizations were a big deal, and really helped get people some jobs.”

Building a Lasting Business Model

In 1945, Elmore passed the baton to his son James Helf, who had just come back to Columbus after serving during World War II. James ran the company until passing it on to his son and Reid Helf’s father, Gary Helf, in 1971. Gary had just earned his business administration degree from Eastern Kentucky University.

“My dad even talks about when my grandfather was in high school, they had a station wagon and they would drive out to Iowa, North Dakota,” Reid Helf says. “They would stay with the parishioners or the pastor at the church, and they would feed them. And they would basically live, kind of, with these church communities for a little while, while they installed and finished these windows. It’s just so different from how it is today.”

While the installation has changed over the years, Franklin Art Glass has largely maintained the same design process since its inception.

“The process is pretty much original. I tell people the big change in the process is we use electric soldering irons,” Gary says, adding that they used gas-powered soldering irons until the late 1960s.

“And florescent lighting,” Reid Helf adds with a laugh.

The company’s big break came in the ’60s, when Wendy’s was preparing to open their first hamburger shop, just down the street from Franklin Art Glass’ second location on Oak Street. Wendy’s hired Franklin Art Glass to help them design and then create a series of stained-glass, Tiffany-style hanging lamps for the restaurant chain. They also made stained-glass wall dividers for some Wendy’s locations with salad bars.

The project, which lasted about a decade, was so big that Franklin Art Glass added an entire department devoted to Wendy’s. In that time, they produced about 45,000 lampshades that were installed in locations across the country, and even a few overseas.

From there, their corporate client list grew to include White Castle, Victoria’s Secret, Max & Erma’s and more.

Towing the Line Between Tradition and Trends

Franklin Art Glass Studios is a German Village hidden gem. Blending in with the surrounding sea of brick on a residential street, the building — which was originally built as an armory and was, at one time, used to store Franklin County’s voting machines — is easy to miss. You may have even parked there without realizing it — The Sycamore restaurant uses Franklin Art Glass’ parking lot for overflow parking after business hours.

But Franklin Art Glass has been on Sycamore Street since the company moved from Oak Street in 1968. The business — which includes retail, ecommerce, wholesale, restoration and custom designs — is housed in a 23,000-square-foot plant with a 12,000-square-foot warehouse. With 21 employees, they’re now the largest stained-glass company in the state.

When walking in the front door — which is stained glass, of course — visitors enter a deceivingly small retail store that gives little indication of the expansive size of the facility that’s the length of a city block. But behind the cozy shop filled with ornamental glassware, like intricate lampshades, and rows of glass samples ranging in color and texture, designers and craftspeople are hard at work on projects, from a single cabinet-door panel to a large stained-glass installation for a church.

Many associate stained glass with religious institutions, and for good reason.

“Just about any church in the area we’ve probably done work for,” Helf Reid says.

One example is the Tifereth Israel synagogue on Broad Street.

“We did work there in the ’20s,” she says. “We did work there in the ’60s, and we did work there in the ’80s. And so that one’s pretty neat, that it has multigenerational work there.”

They also do a lot of custom orders for homeowners, and sometimes that means addressing misconceptions, like this one, Gary says:

“If you put stained-glass windows in,” Reid Helf chimes in and they finish the sentence in unison, “your house is going to look like a church.”

But their window artworks range in style from traditional to modern. When New Albany was being built, they received several custom orders to fit the theme of the Georgian-style homes.

“We see different trends, and you really notice it in residential,” she says. “For a while, Tuscan style was very popular in homes, and we did a lot of grape leaves and Italianate scenes. Now we’ve kind of rolled into doing a lot of filigree-looking designs that look like a wrought-iron-style design.”

The custom studio also handles the company’s restoration work.

“I think stained glass is one of those things — like jewelry, nobody throws it away,” Gary says. “They try to get it fixed or repaired.”

Helf Reid says the amount of new versus restoration projects varies, but at the moment, they’re doing more restoration work than custom orders. And to some extent, it’s because of the age of the city of Columbus.

“A lot of those (early) churches have original windows and are to the point where they’re starting to need attention,” Helf Reid says. “An average window (from that time) lasts 75 to 100 years.”

And now, Franklin Art Glass has been around long enough to begin restoring their own work. They’re currently working on an extensive restoration of glasswork the company created and installed in St. John’s Burry’s Church in Rochester, Pennsylvania in 1928.

“This is a really fun job — we were thrilled to get this job,” Helf Reid says. “I think it’s a really neat experience to see what our work was and to make it look new again.”

“It made for a really great education in glass,” Helf Reid says. “Having seen a lot of different glass a lot of places and knowing a lot of other artists and studios throughout the nation was kind of an indirect exposure to everything. But it was never, like, forced or never pressured, which was really nice.”

By the time she started college at Wittenberg University in Springfield, Helf Reid knew she wanted to come back to Columbus and work at the family business. Founded in 1924, Franklin Art Glass has a rich local and regional history. And even before Franklin Art Glass, her family was making stained glass in Columbus.

“I’m an only child, so it was kind of one of those things where, if I didn’t come here it was OK, but … it would mean having to sell,” she says. “We’re a really small family.”

With her post-graduation plans in mind, Helf Reid decided to study both business and art. She worked with an advisor from each area of study to create an interdepartmental degree, which was then approved by the provost.

“It worked out really well,” she says of her bachelor of arts degree.

Since graduating in 2003, Helf Reid has been continuing her family’s legacy at the Sycamore Street studios. While her title is vice president of Franklin Art Glass Studios Inc., she does a little bit of everything, much like when she was younger. Today, her roles include part-time designer, bookkeeper and marketing and social media manager.

Turbulent Times

Stained glass goes back five generations in the Helf family. It all started with Henry Helf, who worked as the shop foreman at Von Gerichten Art Glass Co. in Columbus until the company closed in 1931.

Henry passed his love of glasswork on to his son Henry “Elmore” Helf, who — along with Wilhelm Kielblock and Wilhelm Kielmeier — founded Franklin Art Glass Studios Inc. on Spring Street downtown in 1924.

At the time, the country was on the brink of the Great Depression, which lasted for about a decade, starting in the late 1920s. Henry wasn’t getting work at Von Gerichten, so he filled his time by drawing intricate window designs for Franklin Art Glass.

“And then they would turn around and use [the drawings] as their sales portfolio or catalog later on,” Helf Reid says. “So it turned out to be a pretty useful tool, that he did kind of doodle so much.”

The economic downtown meant little work for the fledgling company, so Kielblock and Kielmeier left Franklin Art Glass. Kielblock was an artist and had little interest in running a business, anyway. But their departure was amicable, and Kielblock even set up shop at Franklin Art Glass Studios, producing glasswork under his own company, Ohio Trade Studio.

“He did a lot of really neat stuff,” Helf Reid says of Kielblock. “He just kind of produced what he wanted when he wanted, and then we would pay him to do the [jobs] we were doing. And he worked here until his death.”

Despite the Depression, Franklin Art Glass survived and, eventually, thrived. When Kielblock and Kielmeier left, there were less people to pay. Plus, the Helf family already had established connections in the industry.

“Both Henry and Elmore were really involved in the Stained Glass Association of America,” Helf Reid says. “They held the first convention here in Columbus. And we held the 100th convention here in Columbus, back in 2003, as kind of a celebration of that. But I think that being really involved in that kind of national organization — at the time, those trade organizations were a big deal, and really helped get people some jobs.”

Building a Lasting Business Model

In 1945, Elmore passed the baton to his son James Helf, who had just come back to Columbus after serving during World War II. James ran the company until passing it on to his son and Reid Helf’s father, Gary Helf, in 1971. Gary had just earned his business administration degree from Eastern Kentucky University.

“My dad even talks about when my grandfather was in high school, they had a station wagon and they would drive out to Iowa, North Dakota,” Reid Helf says. “They would stay with the parishioners or the pastor at the church, and they would feed them. And they would basically live, kind of, with these church communities for a little while, while they installed and finished these windows. It’s just so different from how it is today.”

While the installation has changed over the years, Franklin Art Glass has largely maintained the same design process since its inception.

“The process is pretty much original. I tell people the big change in the process is we use electric soldering irons,” Gary says, adding that they used gas-powered soldering irons until the late 1960s.

“And florescent lighting,” Reid Helf adds with a laugh.

The company’s big break came in the ’60s, when Wendy’s was preparing to open their first hamburger shop, just down the street from Franklin Art Glass’ second location on Oak Street. Wendy’s hired Franklin Art Glass to help them design and then create a series of stained-glass, Tiffany-style hanging lamps for the restaurant chain. They also made stained-glass wall dividers for some Wendy’s locations with salad bars.

The project, which lasted about a decade, was so big that Franklin Art Glass added an entire department devoted to Wendy’s. In that time, they produced about 45,000 lampshades that were installed in locations across the country, and even a few overseas.

From there, their corporate client list grew to include White Castle, Victoria’s Secret, Max & Erma’s and more.

Towing the Line Between Tradition and Trends

Franklin Art Glass Studios is a German Village hidden gem. Blending in with the surrounding sea of brick on a residential street, the building — which was originally built as an armory and was, at one time, used to store Franklin County’s voting machines — is easy to miss. You may have even parked there without realizing it — The Sycamore restaurant uses Franklin Art Glass’ parking lot for overflow parking after business hours.

But Franklin Art Glass has been on Sycamore Street since the company moved from Oak Street in 1968. The business — which includes retail, ecommerce, wholesale, restoration and custom designs — is housed in a 23,000-square-foot plant with a 12,000-square-foot warehouse. With 21 employees, they’re now the largest stained-glass company in the state.

When walking in the front door — which is stained glass, of course — visitors enter a deceivingly small retail store that gives little indication of the expansive size of the facility that’s the length of a city block. But behind the cozy shop filled with ornamental glassware, like intricate lampshades, and rows of glass samples ranging in color and texture, designers and craftspeople are hard at work on projects, from a single cabinet-door panel to a large stained-glass installation for a church.

Many associate stained glass with religious institutions, and for good reason.

“Just about any church in the area we’ve probably done work for,” Helf Reid says.

One example is the Tifereth Israel synagogue on Broad Street.

“We did work there in the ’20s,” she says. “We did work there in the ’60s, and we did work there in the ’80s. And so that one’s pretty neat, that it has multigenerational work there.”

They also do a lot of custom orders for homeowners, and sometimes that means addressing misconceptions, like this one, Gary says:

“If you put stained-glass windows in,” Reid Helf chimes in and they finish the sentence in unison, “your house is going to look like a church.”

But their window artworks range in style from traditional to modern. When New Albany was being built, they received several custom orders to fit the theme of the Georgian-style homes.

“We see different trends, and you really notice it in residential,” she says. “For a while, Tuscan style was very popular in homes, and we did a lot of grape leaves and Italianate scenes. Now we’ve kind of rolled into doing a lot of filigree-looking designs that look like a wrought-iron-style design.”

The custom studio also handles the company’s restoration work.

“I think stained glass is one of those things — like jewelry, nobody throws it away,” Gary says. “They try to get it fixed or repaired.”

Helf Reid says the amount of new versus restoration projects varies, but at the moment, they’re doing more restoration work than custom orders. And to some extent, it’s because of the age of the city of Columbus.

“A lot of those (early) churches have original windows and are to the point where they’re starting to need attention,” Helf Reid says. “An average window (from that time) lasts 75 to 100 years.”

And now, Franklin Art Glass has been around long enough to begin restoring their own work. They’re currently working on an extensive restoration of glasswork the company created and installed in St. John’s Burry’s Church in Rochester, Pennsylvania in 1928.

“This is a really fun job — we were thrilled to get this job,” Helf Reid says. “I think it’s a really neat experience to see what our work was and to make it look new again.”